What We Don’t Know About Total Knee Joint Replacements

Total artificial knee joints are a lifesaver for people with severely arthritic knees. There is much about them to love, parts to hate, and even more that is unknown.

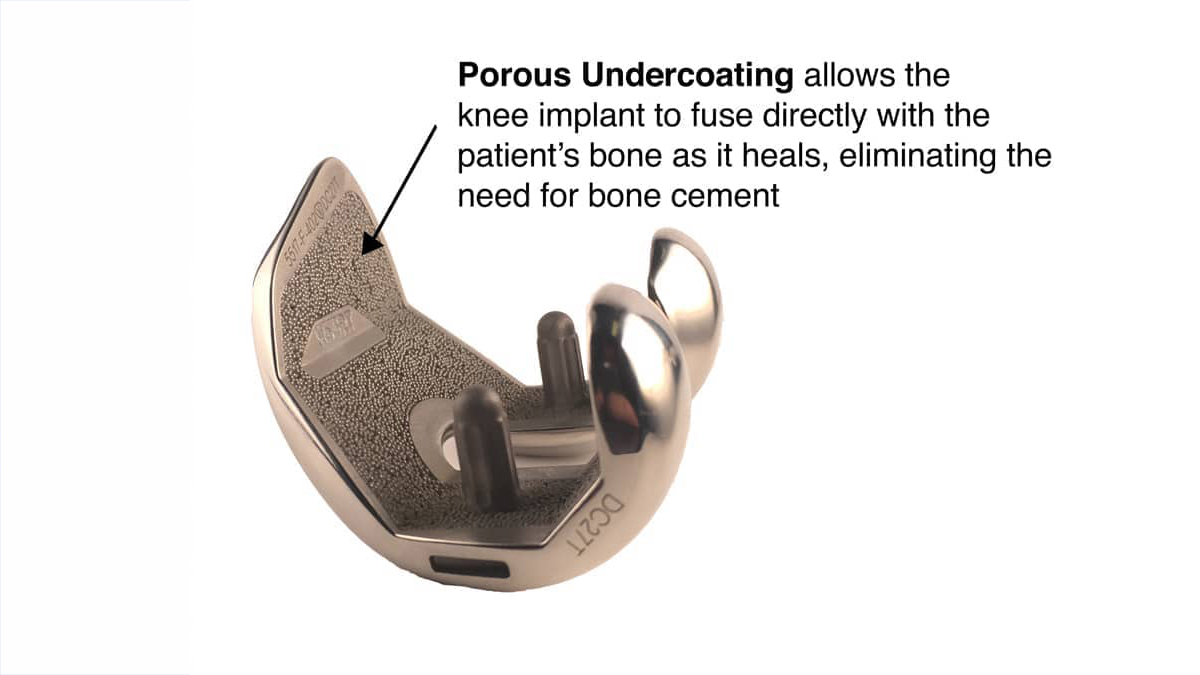

Modern versions of metal and plastic knee joints were invented in the 1960s. The design evolved in the 1970s as the total condylar, meaning covering both sides of the joint with a metal cap. Until the early 1980s, each of the metal implants was held to the bone using PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) cement. Later on, porous surfaces were adhered to the undersurface of the implant to permit the patient’s own bone to grow into the metal, thus fixing the implant to the patient.

The arc of development of each of these three aspects of the implants—their shape, their function, and the fixation to the patient—continues to evolve, with the goal of replicating a normal knee. Unfortunately, nothing fully succeeds. Here are a few highlights of that arc—or low lights, depending on your perspective.

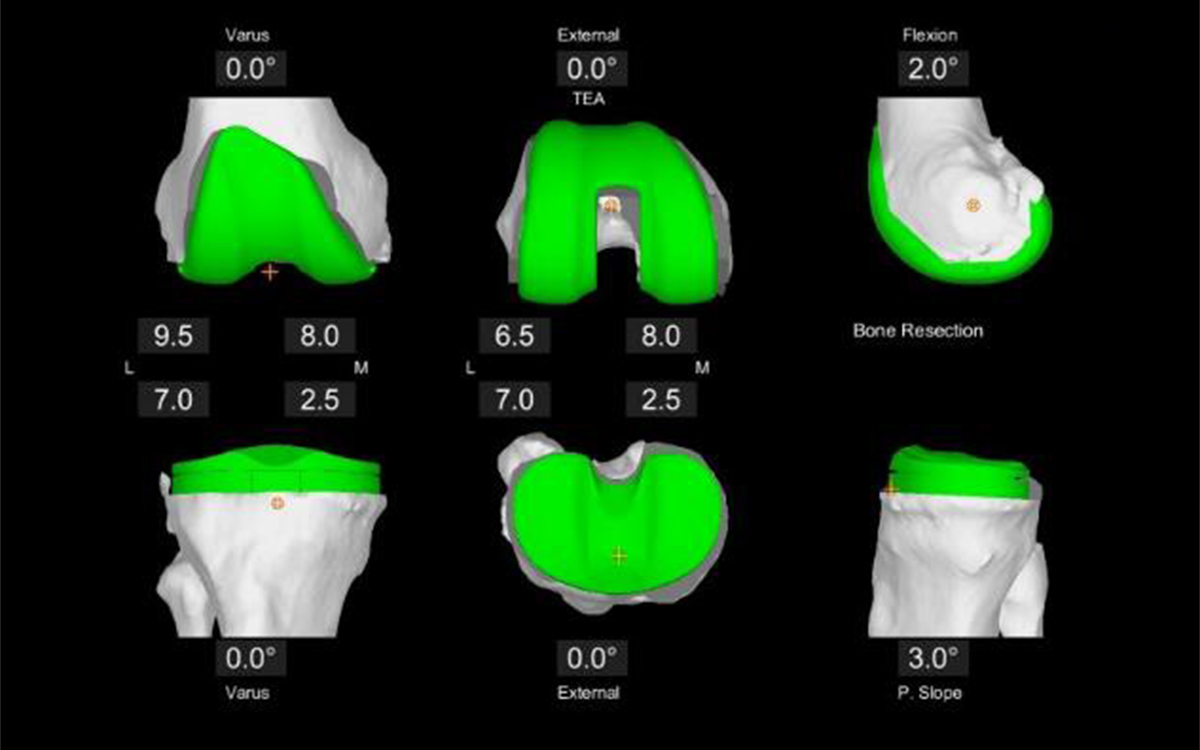

The shape and sizes of knee implants are generalized to the entire population. This means that there are few sizes on the shelf and the surgeon is required to shave the patient’s knee to match one of those sizes. Traditionally, saws and cutting guides were used to do this and most surgeons still use them. I did until about 10 years ago. That is when surgical robots came along, featuring 3D mapping of the patient’s knee and a cutting tool that removed only a minimal amount of bone to allow surgeons to perfectly fit the implant to the bone. This massively improved surgical precision permitted us to eliminate the bone cement as patients reliably grew their own bone into the porous, bone growth-friendly undersurface.

Confident of the fixation, and eliminating the risk of cement loosening, we permitted our patients to return to running and impact exercises. So far, so good. But 10 years is not a lifetime, and we really don’t know what the future will bring.

The shape of the femur and tibial component of the artificial joint permits a nearly full range of motion of the knee. However, the motion of the normal knee includes both bending and rolling back, with unique rotational movements for each patient. The artificial designs do not yet perfectly mimic that complex set of motions. As a result, almost all the artificial knees I examine (those more than 10 years old) have stretched out the side ligaments of the joint and the surrounding tissues, even though they still function pretty well. We don’t yet know the consequences of that stretching, and we don’t yet know how to make better designs.

The artificial knee joint also comes with a high molecular weight polyethylene tray that replaces the meniscus and permits the femur to roll on top of the tibia. While the company that makes them says this is a 30-year implant, our patients are pushing their range of activities with endurance events and multi-hour and multi-mile impact sports. Fortunately, the tray is replaceable and hopefully, there will be better ones in the future.

We believe that the old advice to “go home and rest your knee” and avoid impact sports after artificial joint surgery led to both more muscle weakness and more osteoporosis as people aged—as well as to more implant loosening. We now counsel our patients to increase their exercise, build their muscle and bone to enjoy every year available.

In fact, we don’t know when your knee will fail or when you will die—but we do hope to have you exercising with a smile on your face and dropping dead at age 100, playing the sport you love.