Repair Once, Sometimes Cut Twice

Once failed, should you be repaired twice? Stories from the shoulder, knee, and ankle.

Some tissues respond well to primary repair, by which we mean suturing the torn tissues together. Most of these tissues, however, fail to respond well to repeat repair. Here are a few examples.

The meniscus tissue is the key shock absorber in your knee. When chronically torn, or if portions are removed, arthritis develops. We are biased toward immediate suture repair whenever possible and have developed novel ways of repairing tears that were previously thought to be irreparable. When pushing the limits, we do see failures. Either because the tissue was just too damaged initially or due to repeat injury. If we try to suture the meniscus tissue again, it sometimes fails—more often than we would like. The torn repair tissue is simply not healthy enough to take the stresses of the knee. So now, rather than re-repair, we often replace the severely damaged meniscus with a donor meniscus.

The shoulder labrum and the rotator cuff are also commonly repaired tissues.

The labrum (part of the key ligament-labrum joint complex) very often tears with a shoulder dislocation. Second-time repairs are not as successful. So we often combine the capsule of the joint with the labrum to provide some pants-over-vest type repair.

The rotator cuff has a similar fate. When torn in a young person, the tissue is traumatically injured but otherwise healthy. These tissues usually heal well. Older peoples’ rotator cuffs have a decreased blood supply and tissue is often degenerative. When we repair these tissues, we often use strong permanent stitches that squeeze the tissue tightly into a prepared bone insertion site. Unfortunately, the squeezing cuts off more of the blood supply. So when these repairs fail—which they do, up to 30% of the time in people over 50 years of age—a repeat repair has a high likelihood of failure. To combat this risk, we now augment the repairs with donor tissue patches and growth factor stimulation. However, this strategy is only partially successful and has much room for innovation.

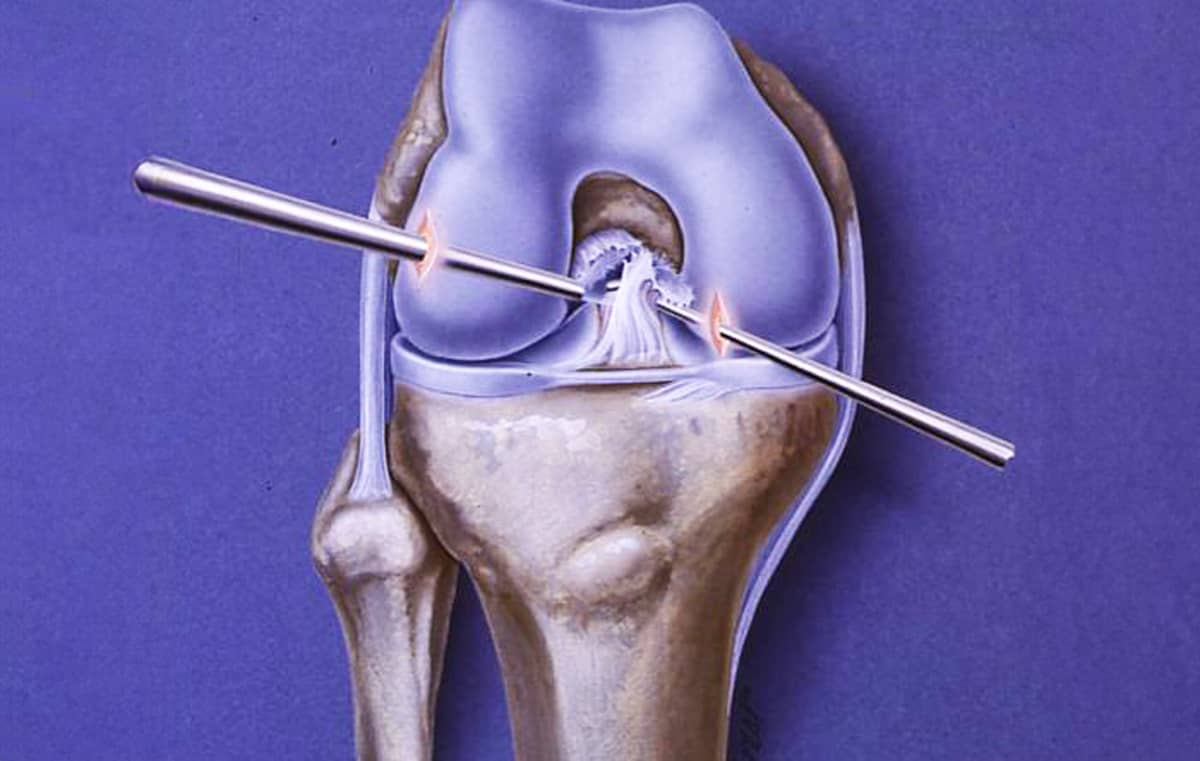

The knee joint anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) can sometimes be suture-repaired directly. With the advent of collagen tampons, which are added to the ligament to augment healing, there is new enthusiasm for this procedure. When the repairs do fail, the collagen fibers of the ligament are fatally disrupted. Reconstruction (replacing the ligament) with tissues from other parts of the injured patient or with donor allografts is required to create a stable knee. Today, with the addition of grafts on the outside of the knee, these reconstructions have a much higher success rate.

The cartilage of the ankle—and the knee, for that matter—can be repaired primarily with grafts composed of a paste of bone and articular cartilage. These grafts usually heal well. If arthritis sets in, though, a progression of the damage can occur. Fortunately, repeat cartilage grafting is usually successful as “no bridges were burned” during the initial repair procedure.

The bottom line here is this: When good initial repair occurs, protect it. Strengthen the muscles around it. Create fitness for the entire body. The first repair is the best. Getting the great results we want in a second go-round requires creativity, innovation, and good luck. Sound like a good marriage? It should—our joints are our life partners.