Breaking Bad

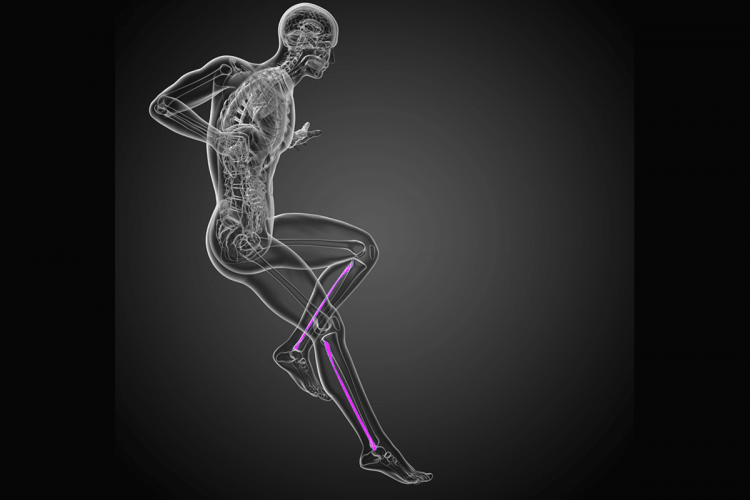

Bone fractures around the knee fall into two groups: Those that lead to arthritis and those that heal just fine. Here is a brief guide to which is which.

When a fracture of a supporting bone such as the tibia in the knee occurs from trauma or excessive load, a key variable is whether or not the crack is wide or narrow, and whether the surface of the joint is intact or depressed. Since the coefficient of friction of the smooth articular cartilage that covers the ends of the bones in joints is five times as slick as ice-on-ice, any disruption increases the friction, wears away the surface, and leads to arthritis.

Separations or depressions of more than 2 millimeters are significant enough that they warrant immediate surgical repair as an attempt to restore the congruency of the joint surface.

Fractures from trauma to the knee joint can be described as clean breaks, where a single crack occurs without damage to surrounding soft tissues (such as the meniscus or ligaments) and without depression of the surfaces or complex fractures with multiple fracture lines and a variety of associated injuries. Defining which is which often depends on the quality of the imaging techniques available. X-rays show the obviously bony fractures, CT scans define the bony injury patterns and degrees of depression (and permit 3D models to be computer generated), while high-quality MRIs define the soft tissues the best. It is common for us to obtain all three to refine our repair techniques. Each one—X-ray, CT, and MRI—has advantages and limitations. Given that we cannot accept more than a couple of millimeters of offset and that the repair of the soft tissues is as important as the healing of the bone, an incomplete data set of information may lead to an unfortunate outcome.

Fractures from mild impact, or stress fractures, raise the question of underlying bone disease, weakness, or osteoporosis. Here we must understand the biology of the patient to find the cause of the bone softness and treat it in conjunction with the injury. Only resistance exercise has been consistently shown to build bone, and relative disuse always leads to bone weakness. Unfortunately, the drugs for treating osteoporosis have not been overwhelmingly successful. Other causes of bone weakness, such as dietary restrictions and hormonal imbalances, must be discovered and corrected. The challenge with a stress or insufficiency fracture is how to apply just enough force to stimulate the bone cells to heal without further deforming the bone. We often do this with pool exercises, where the water provides the resistance to the deformation of the bone during healing. Outside stimulation—by electrical current, ultrasound, magnetic fields, and vibrating plates—play a supportive role to exercise and are helpful in many cases.

Fractures from major trauma and those where the ligaments, meniscus, and articular cartilage are damaged heal the best when put back together as anatomically as possible. Immediate surgery is often the best approach, with a careful reconstruction of all the injured tissues. It may come as a surprise to some, but the skill set and biases of the surgeon is the first component of optimizing the outcome. If the surgeon is an athlete or understands the needs of athletes, he or she is more likely to repair and reconstruct the tissues necessary for high-level sports. If the surgeon is a trauma surgeon alone and not particularly attuned to the demands of an athlete, the bones may heal but the joints may not work as well as needed.

The second most important factor is the attitude of the patient. Upbeat patients with “can do” attitudes, who get themselves immediately to physical therapy and use their injury as an excuse to return to sports better than they were before they were injured, are the ones who heal the best. Patients who feel victimized by the injury are often immobilized psychologically and physically, leading to poorer outcomes.

Ultimately it is not just the injury, and not just the surgeon, and not just the patient. It is the interplay of all three that heals the patient. Breaking bad does not have to mean healing worse.