What We Don't Know About the Shoulder

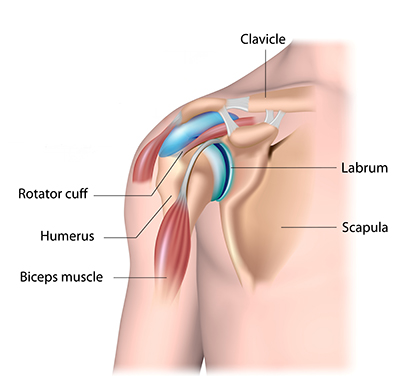

The shoulder is a shallow ball and socket joint. The tendons that hold it together are injured so frequently that rotator cuff repair has become the second-ranking major ambulatory surgery in the United States1 (over 460,000 performed yearly2). The bummer is that the failure rate of these surgeries is disappointingly high.

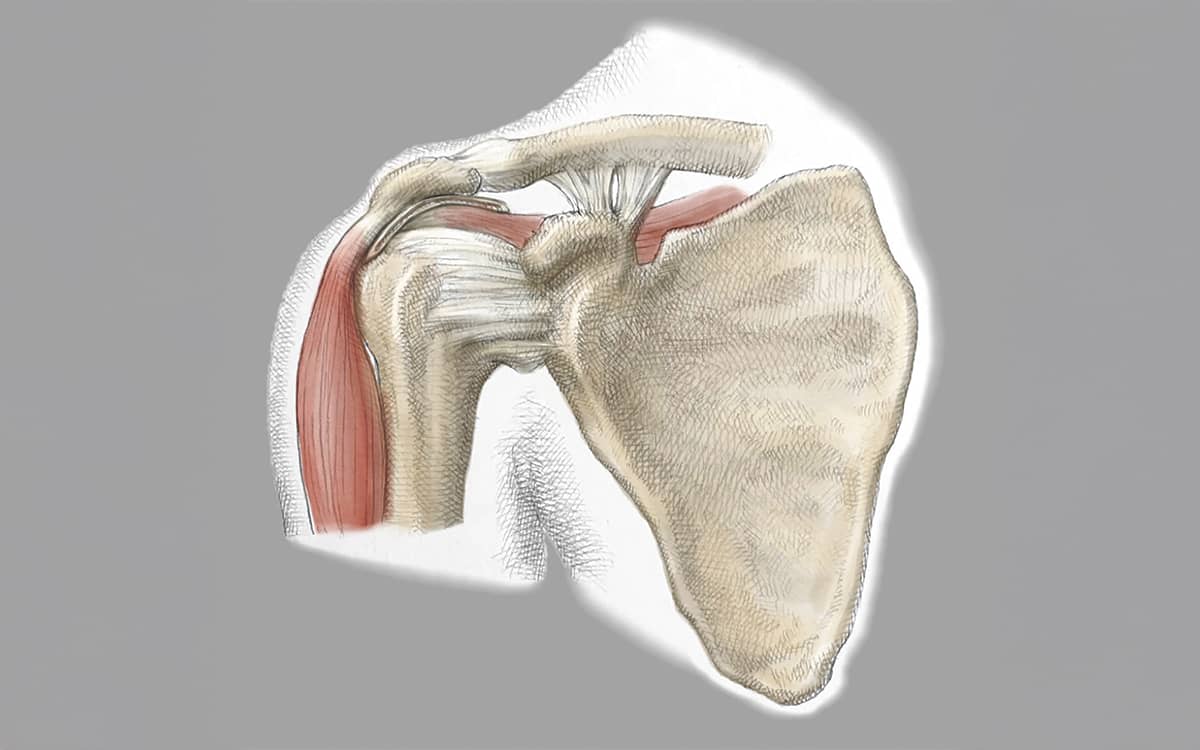

The tendons of the rotator cuff extend from four main muscles: the infraspinatus (below the spine of the scapula), the supraspinatus (above the spine on the top of the shoulder), the subscapularis, and the teres minor. The blood supply to these tendons diminishes due to aging, injuries, and degenerative diseases. To repair these tendons, we compress them with strong sutures in an effort to squeeze them onto the bony surfaces where they naturally insert. The repair sutures further cut off the already limited blood supply.

This is where all the unknowns come in. We don’t know how to repair the tendons without compressing them. We don’t know how to reliably increase the blood supply. And we don’t know how to take torn, degenerated tendons and stimulate healthy collagen replacement. And without knowing these answers, we cannot hope to significantly improve the tendon repair success.

We do make admirable efforts to solve these problems. We bloody the bony insertion sites to bring in a better blood supply. We add growth factors and lubricants to improve the healing. And we add patches of dermis, tendon, and other materials to thicken and (hopefully) strengthen the repairs. Yet none of these efforts has significantly changed the outcomes.

And it is not just the rotator cuff tendons that confound us. The ligaments of the shoulder are attached to a meniscus-like tissue called the labrum that acts as a bumper to keep the shoulder in place. When the shoulder is dislocated—usually from a fall—the labrum is torn and the capsule of the joint is often stretched out. We know how to repair the labrum and tighten the capsule, yet the optimal repair is still elusive. If we repair the labrum too high on the glenoid surface (the socket in the shoulder blade where the head of the humerus rests), the shoulder becomes too tight and loses motion. If the repair is too loose, the shoulder subluxates or shifts in and out. And despite much innovation in the types of suture anchors used to attach the labrum to the bone, the success of arthroscopic repair has not proved to be much better than the old open surgery.

The biceps tendon (the muscle in the forearm) also plays a huge role inside the shoulder. Its upper end is attached to two of the shoulder bones and is often thought to produce pain when inflamed. Surgeons are divided between those who believe the biceps should be cut free from its attachment, those who believe the biceps should be cut then reattached at a lower point, and those who don’t believe the biceps should be cut at all. Remarkably, the data is about the same for all three groups, and no one knows the right answer.

We have much to learn about the tissues surrounding the shoulder joint. Fortunately, most patients do better after repair of the damaged tissues and most return to sports. However, if knowledge is power, ignorance is aggravating. Ask anyone with a shoulder injury just how painful and annoying it is, and you will find out why we are so passionate about pushing forward the science of tissue healing.