What We Don't Know About the Meniscus

The meniscus is the key shock absorber in the knee joint. Torn 800,000 times a year in the US alone, it is a major cause of disability. Here are the good and bad realities of a meniscus tear.

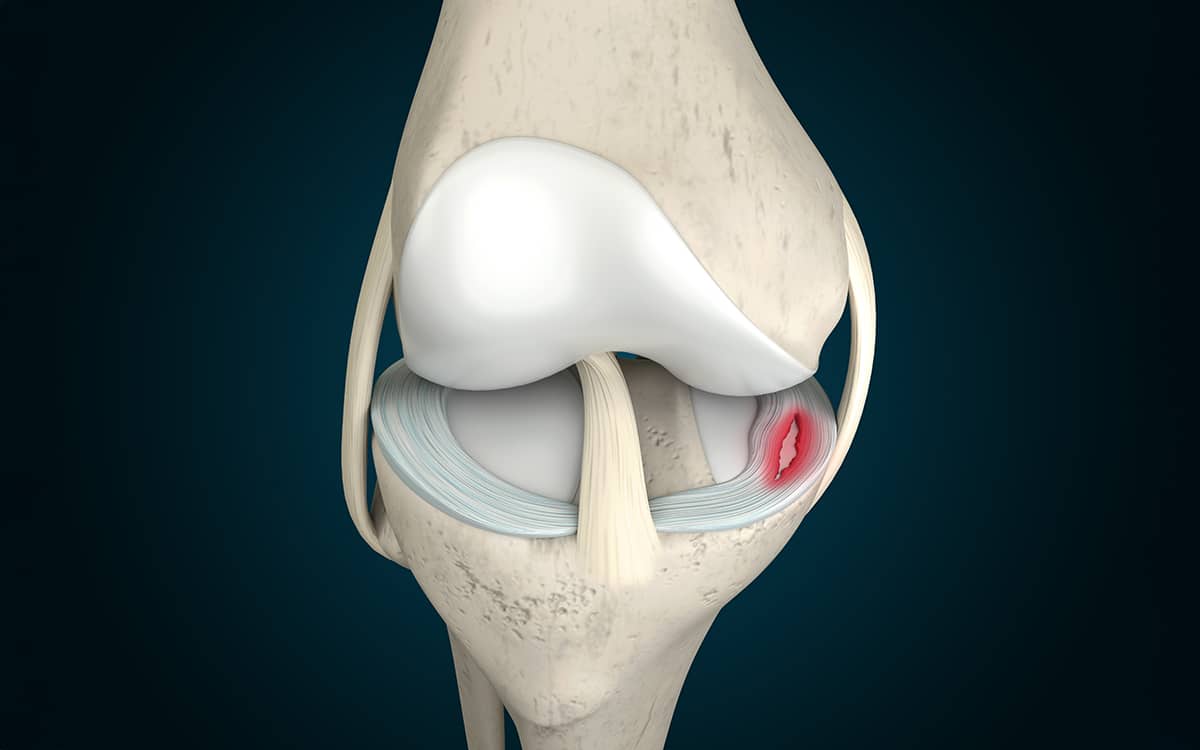

The meniscus is a fibrous tissue sitting between the femur and the tibia (shinbone). Since we take 2-3 million steps per year in normal walking, the meniscus takes a huge amount of force and distributes it smoothly across the tibial surface. Once torn, those forces are concentrated on a smaller area of the tibia, leading to overload and eventually arthritis.

The torn, fibrous meniscus tissue exposes its collagen fibers to the knee joint’s synovial fluid (the joint space lubricator). Cells—some of them stem cells—rush from within the injured meniscus, from the synovial lining, and from the fluid itself to initiate the repair process. It usually fails, most likely due to the forces and rotations of the knee that keep the edges of the tear apart.

If treated early, the freshly torn tissue can usually be repaired with sutures and the repairs augmented by cells from the bone marrow or blood clot made from the patient’s peripheral blood. Even old tears can be freshened up with a shaver and repaired. It used to be thought that only the outer portion of the meniscus—where the best blood supply exists—could be saved. But techniques for repairing most meniscus tears are now available. The desires of the patient, the skill of the surgeon, and the realities of insurance, work, life, and sports often determine which treatment is applied.

The sciences of meniscus repair, biology, biomechanics, and regenerative medicine have advanced dramatically. Scaffolds of collagen can be used to regrow missing sections, while donor tissues are available to fully replace the meniscus when it is lost due to injury, surgery, or arthritis.

Yet the practice of deploying each of these more advanced techniques is remarkably low. Eighty percent of all meniscus tears are resected and not repaired, regenerated, or replaced, even in the United States. The loss of tissue dooms the knee.

We don’t know how to change this. The science is clear, the techniques are taught at every orthopaedic meeting, and the tools are available. But the short-term benefits of resection—which include low cost, an early return to work and sports, and ease of technique—trump all the benefits that we know patients would receive from the newer techniques.

Having spent a lifetime on the science of tissue regeneration, I do know that the need for restoration of normal anatomy will not decline. As the benefits offered by new strategies continue to demonstrate success, the adoption of these techniques should become irresistible.

Meniscectomy vs Meniscus Replacement - Meniscus Tear Treatment Options

The meniscus is the key force distributor of the knee joint. When torn, it fails to protect the tibia from the forces exerted by walking and sports. Pain results. If the surgeon removes the torn part of the meniscus, the pain is often relieved for a while—until the cartilage and bone underneath wear down. The solution? Save the meniscus.