Why “Bucket Handle” Tears of the Meniscus Fail to Heal

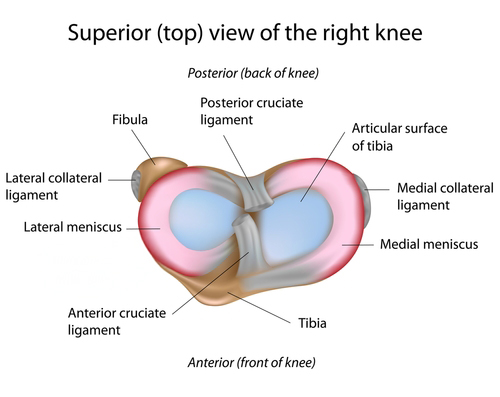

The meniscus consists of a pair of C-shaped fibrous shock absorbers located inside the knee joint. Torn frequently, the meniscus causes all kinds of problems, some of which are fixable. Here is a look at a few of the issues.

A healthy meniscus is divided between a medial (i.e., inside the knee) fibrous tissue and a lateral outside tissue. Its wedge-shaped construction absorbs the forces of walking and running, stabilizes the femur (thigh bone) on the tibia (shin bone), and protects the apposing articular cartilage which covers the ends of those bones. It has a rich supply of blood, more so at its periphery. It also contains unique stem cells and specific meniscus cells (called fibrochondrocytes), nerves, and collagen fibers organized in a circumferential fashion with radial tie rods to hold it together.

Due to the rolling back of the femur on the tibia with rotation and shear during walking, running, and jumping, the tissue often gets pinched and torn. Certain types of tears are more amenable to suture repair than others. Our guideline has been that if there is healthy tissue, a stable repair can be achieved. Almost all meniscus tears have the potential to heal, especially with the addition of growth factors and marrow cells. This is different from the classic surgical training, which holds that only the peripheral portion—with the most robust blood supply—can be repaired.

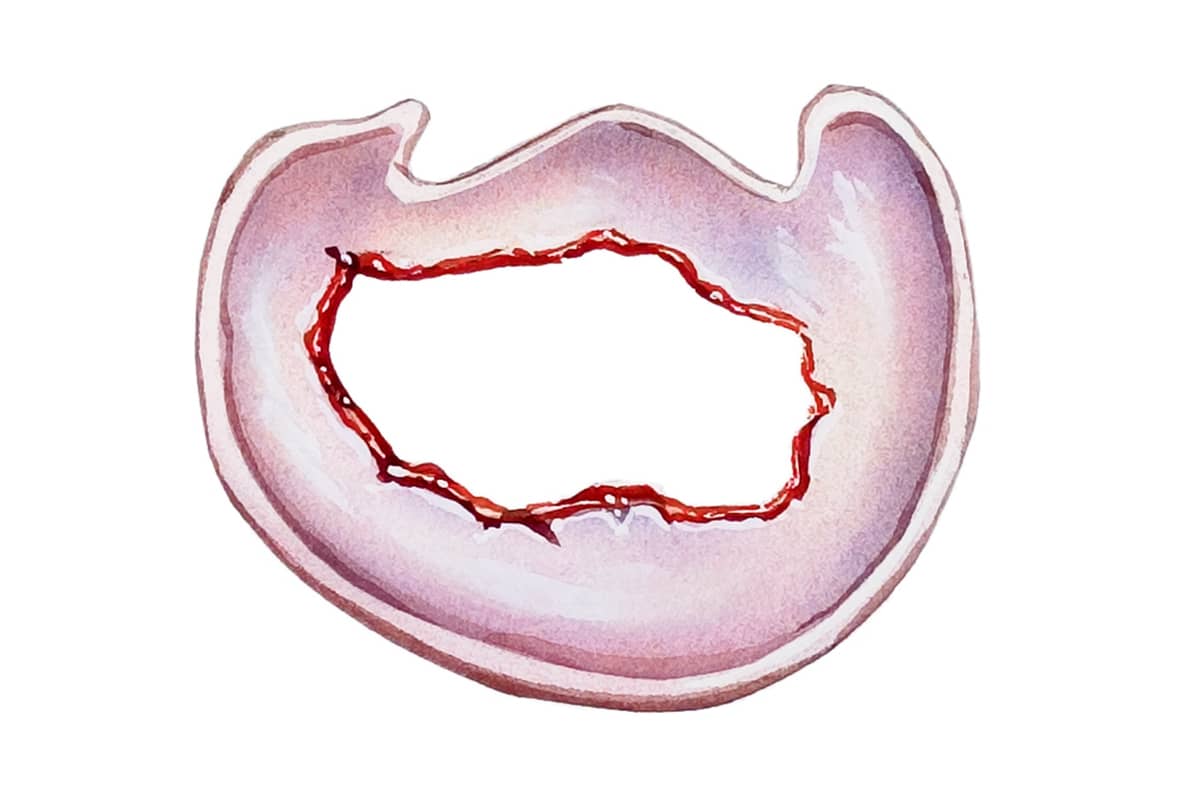

Tears that involve complete displacement of a portion of the meniscus, however, have a high failure to heal rate. These tears present as a broken-off piece where the inner portion is displaced into the middle of the joint while still attached at the horns of the meniscus, forming a “bucket handle” shape.

This occurs, in part, because the torn tissue that is displaced was fundamentally abnormal before it fully tore. The collagen fibers were either diseased with degeneration or—in the case of discoid meniscus in children—were not formed correctly at birth. No matter how many stitches we put in, or how many cells and growth factors we add, repairing abnormal tissue leads to poor results.

As we age the chemical components of the tissue evolve, resulting in less elastic tissue and a reduced ability to protect the joint. The older the tissue and the longer it has been torn, the higher the stiffness and degenerative components. As we are seeing more and more tears in patients in their 70s (mainly from Pickleball) we are evolving our thinking and developing new techniques to protect these patients’ joints so that they can continue to play.

That said, most tears are complex tears: A portion of the meniscus may be displaced, but the remainder—though it is torn from mechanical stress—is healthy. Most of these tears receive a combination of minor resection and suture repair. Since the loss of any volume of the meniscus leads to forced concentration on the tibia, wearing away of the articular cartilage, and eventual arthritis, we are driven to save as much of the tissue as possible. If a significant amount is lost, we replace it with donor tissue.

Recently published data by the Stone Research Foundation in patients over 50 with significant arthritis demonstrated that if the arthritis is treated with a grafting technique, the meniscus can be successfully replaced. This allows the patients to delay, and often avoid, joint replacement. Many return to sports.

The bottom line is to identify the tissue that can heal (the earlier the better), suture as much as possible, add growth factors and release marrow cells, and rehab the patient with the intention of preserving the joint and returning to sports. A person with healthy tissues is much happier than one without.