ACL Repair Revisited

All ACL surgeons are getting the call: Can my ACL be repaired instead of replaced? The answer is, sometimes.

Why? Here’s what the ACL is, and why a surgeon’s repair strategy is not always obvious.

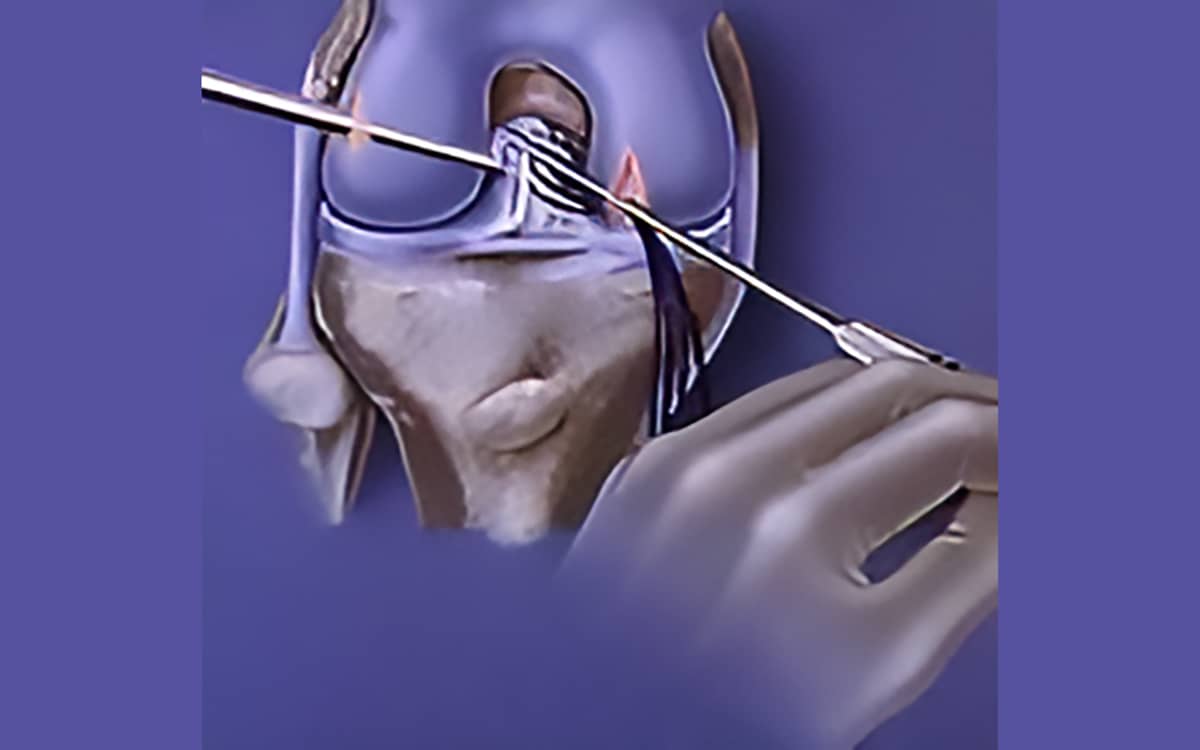

ACL, the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee joint, extends from the femur to the tibia in the middle of the joint. A tight weave of collagen fibers in the shape of a band, it is nourished by a rich blood supply, cells that produce collagen, nerve fibers, and a structure that permits flexion, extension, and rotation of the knee joint through a wide range of motion.

The ACL often ruptures in skiing, basketball, football, soccer, and other twisting and impact sports. Landing with the femur and tibia going in abnormal directions, taking off with torque on the knee joint, being hit from the side in football, or hyper flexing or extending in skiing can all lead to rupture of this critical ligament. And when the ACL is torn, the knee often becomes unstable. This leads to a high rate of meniscus and articulate cartilage injury.

The drive to fix the ACL is informed by the realization that people with an unstable, ACL-dependent knee go on to further damage when they return to sports and especially have difficulty returning to pivoting and twisting sports. For this reason, the torn ACL has a long history of repair and reconstruction techniques, over many decades, but with mixed success.

Primary ACL repair began in 1895 by Sir Arthur Mayo-Robson and has evolved over time. Unfortunately the ACL, like a climbing rope, has a unique construction of fibers. When injured, these internal fibers rupture—even when it appears that just a mild sprain has occurred. The goal of repair is to stimulate new collagen formation that magically replicates the unique formation of collagen within the ligament itself.

Sometimes the tear occurs from the proximal or femoral side of the ACL, pulling off a small portion of bone with it. Because of the relationship between the ligament strength and the osteoporotic bone, this pattern most commonly occurs in women over 35 years old. In our own study of 50 ACL primary repairs, women over 35 did the best. All young males re-ruptured their ligaments when they returned to sports. Thus we restricted primary repair years ago, except in unique cases.

What we did learn is that ACL repairs, when augmented with additional tissue, can go on to heal at a higher rate than ACL repairs alone. ACL repairs augmented by extra articular support (grafts on the lateral side of the knee) can do better than primary repairs alone. In fact, the lateral extra grafts are now used for almost all ACL reconstructions, where the ligament is replaced with another tissue since the extra graft lowers the re-rupture rate to single digits.

The recently developed BEAR technique (Bridge-Enhanced® ACL Restoration) adds a collagen tampon to the ACL in the hopes that new collagen will form more readily and help the ACL ligament heal itself. The collagen tampon is augmented with a permanent set of sutures, which may provide the primary protection of the ligament and facilitate healing.

This unique, careful balancing of protection and healing is the dance a surgeon must perform to provide the ideal healing environment. Too much artificial material and the graft heals with scar tissue. Too little and it sometimes stretches out.

There are now many more ways to stimulate healing in tissues. These include PRP bone marrow stem cell release, and resorbable strong collagen sutures that may dissolve over time, permitting the collagen of the ACL to take over in a graduated fashion.

Since ACL reconstruction using donor tissue (from the same patient) creates a second site injury and has a failure rate that may be as high as 30% in young patients, the enthusiasm for novel techniques in ACL repair is warranted and worth pushing the limits for.

So encourage the science to continue and the enthusiasm for pushing the limits to grow. While repair and reconstruction of injured ACLs have not yet led to normal knees, a repaired joint is still usually much better than an unstable one—which is true of most injuries to our exposed bodies.

ACL Reconstruction Surgery Explained & Picking The Right ACL Graft

Dr. Stone shares the recent innovations in ACL reconstruction that lead to more successful patient outcomes and return our patients to the activities they love fitter, faster, and stronger than before their surgery.