Delaying Knee Joint Replacement

Hear From Our Patients

Athlete delays knee replacement 15+ years with the BioKneeKnee joint replacement is a godsend to those with severe, life-limiting arthritis. In a perfect world, everyone would choose it, rather than living with pain. But because there is a significant revision rate of the primary surgery and because the first joint is always the best, there are real reasons to delay a knee joint replacement—and other reasons not to. Here is the complicated story.

Knee joints become arthritic due to inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid, gout, etc.), genetic diseases (osteoarthritis), and trauma (loss of the meniscus cartilage, ligaments, fractures). Ninety-seven percent of knee joint arthritis is due to osteo and traumatic arthritis. The most frequent story we hear is that someone injured their knee in high school or college, had the meniscus resected and the ligaments operated on, and now—20 years later—have disabling pain in one or more parts of the knee. If that person is under 60 years old and undergoes a traditional knee replacement, with cement to hold in the components and significant bone resection, there is a worrisome revision rate (see graph).

Lifetime risk of revision after total knee replacement Plot showing estimates of lifetime risk of total knee replacement revision against age at the time of primary total knee replacement surgery.1

Fortunately, the options have dramatically improved.

If the arthritic knee is not bone-on-bone, providing there is still some joint space, a biologic knee replacement can be considered. A BioKnee involves repairing and regenerating the damaged articular cartilage (we use a paste graft technique to do this), and replacement of the meniscus and ligaments if missing. Our recent data, presented at the Orthopaedic Research Society annual meeting in 2023, demonstrated that meniscus replacement, a key component of the BioKnee, in patients with arthritis between the ages of 50-70 years old, delayed artificial joint replacement an average of 8.8 years and in 41% of patients helped them avoid it completely for up to 25 years.2

If the knee is bone-on-bone in only one compartment (most common), a partial knee replacement can be performed. Thanks in part to the precision of surgical robotics, partial knee replacements for all three compartments (the medial, lateral, and patellofemoral joints) have superb outcomes in returning people to full sports. A recent 56-year-old patient of ours ran across the United States with two partial knee replacements. Others have returned to marathons, tennis, and other previously forbidden sports.

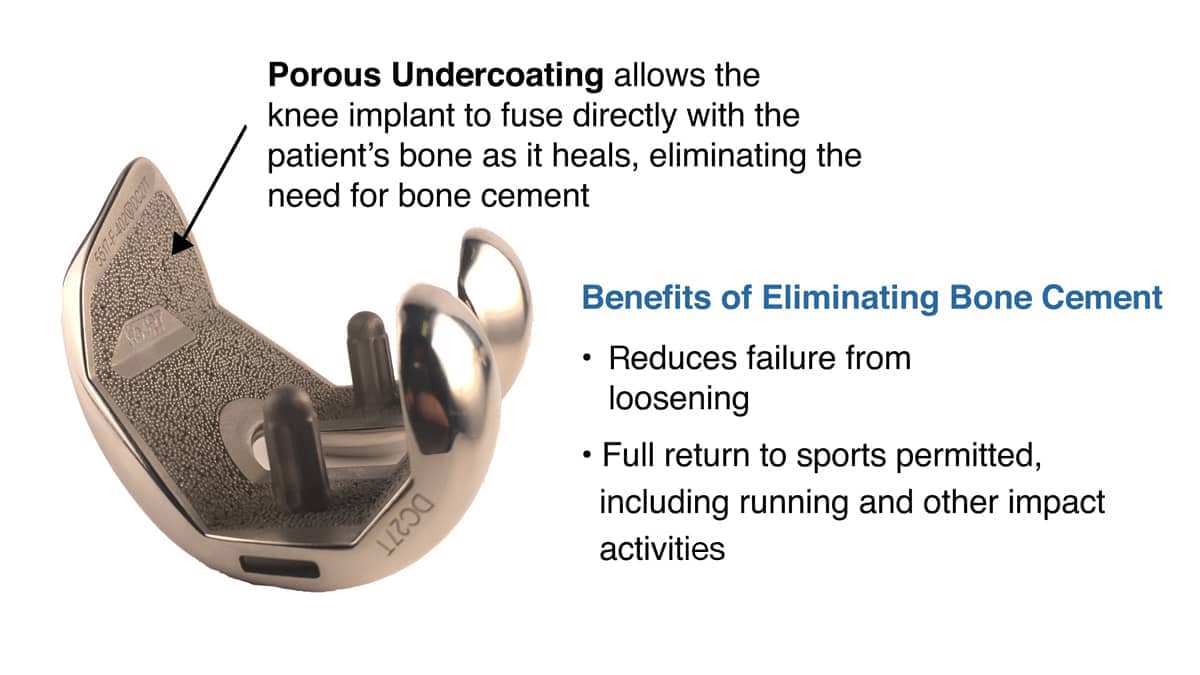

Traditional artificial knee replacement involves significant bone resection with metal components cemented into place. Doctors advised these patients not to do impact sports and protect their knee replacement. However, when an artificial replacement is necessary—due to arthritis in multiple compartments of the knee—we now use a robot to produce minimal, precise bone resection. This strategy, combined with newer knee implants that have porous undersurfaces permitting natural bone ingrowth to fix the devices to the knee, eliminates the need for cement.

With no cement, there is no concern about loosening and, therefore, no reason not to return to full sports—even with a complete resurfacing of the knee. We rarely need to resurface the kneecap, however, as the data on kneecap resurfacing with total knee replacement has shown that there is no difference in outcome, but a higher complication rate with knee cap replacement.

And avoiding surgery altogether is becoming quite common. We have many patients who benefit greatly from our “cocktail” of anabolic injections and hyaluronic acid. For some people, the injections are so potent that the symptoms of arthritis are reduced tremendously. These patients see us regularly before the ski season, asking for their annual “lube job” so they can continue to ski on their arthritic knee.

Never let a knee ruin a great time. There are so many good options available, and life is so precious and so short, that the time to play is now—and forever.

References

1 Bayliss LE, Culliford D, Monk AP, et al. The effect of patient age at intervention on risk of implant revision after total replacement of the hip or knee: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1424-1430. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28209371/

2 Stone KR, et al. Meniscus Transplants in Patients Over 50 Years of Age. ORS 2023 Annual Meeting Paper No. 1481 https://www.ors.org/transactions/2023/1481.pdf

Dr. Stone Explains Why You Likely Don't Need A Knee Replacement

Most orthopaedic surgeons in the US offer total knee replacement as the ONLY solution to an arthritic knee. While knee replacement may be the right choice for some, our experience shows that many patients can achieve better outcomes with less invasive procedures that preserve more of the natural joint—leading to a more natural feel, quicker healing, and improved performance.