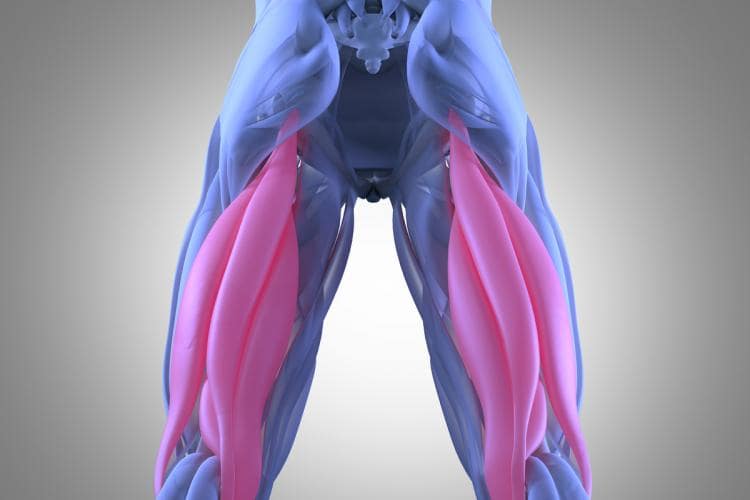

Hamstrings

The dreaded “hammy” is the tearing of the muscle or tendon fibers of the powerful hamstring muscles at the back of the leg. It’s dreaded because the pain is sharp, and the recovery can be long. Here is what’s known and what’s new:

The hamstrings are made up primarily of three powerful muscles: the biceps, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. They cross both the hip joint and the knee joint, flexing the knee and extending the hip. Most importantly, they balance the contraction of the quadriceps thigh muscle, permitting normal walking and running. When they are injured, all the mechanics of the lower extremities are altered. If they are removed to be used as donors to replace the ACL, the deficiencies can be permanent.

A sudden extension of the knee or flexion of the hip leads to the overstretching of these muscle or tendon fibers. Given that almost all leg motions involve the hamstrings, it is nearly impossible to completely rest or protect the injured tissues during the healing phase.

Two basic outcomes thus occur. One involves the muscle tear alone. Small tears can and do heal on their own, with few consequences. Larger tears take months to fully heal and often do so with considerable amounts of scar tissue. This leads to tight muscles and restrictions of motion.

If you could magically miniaturize yourself to watch the healing process, you would see blood rushing to the injury site carrying stem cells. These cells direct the healing process by calling in specialized cells named macrophages, which eat away the torn, dead muscle fibers. Myocyte cells (unique to the muscle) and fibrocytes (which are central to soft tissue repair) pour out new collagen molecules. These then form into fibrils, eventually mending the torn ends of the collagen fibers. This complex sequence is heavily influenced by the amount of tension to which the injured tissue is exposed. Without tension, disorganized collagen structures—scar tissues— form. With just the right amount of tension, new layers of collagen fibers form the correct structure for muscle or tendon to heal.

We’ve learned that the keys to healing are augmenting the number of stem cells at the site of injury and providing force to stimulate the torn tissue ends. This is now done with injections of stem cells, along with additional growth factors that stimulate the process of healing; by soft tissue massage to the torn muscle to remove the excess swelling that resulted from the initial bleeding; and by starting an exercise program that provides just the right amount of tension without distortion of the healing fibers.

The healing process is similar if the injury involves not just the muscle but also the tendon insertion of the hamstrings onto the bone of either the pelvis or the knee. But when a significant amount of tendon is ruptured, it is best repaired surgically—as no amount of bleeding and scarring alone can reproduce the normal anatomy of a major ruptured tendon connected to a massive muscle.

Early accurate diagnosis, with a physical exam and an MRI, is the first step for interventional therapy. Stem cell injections or surgery are the best next steps for athletes wanting to return to full power. Since we’ve come to understand that the growth factors and healing environment for muscle are different from those for tendons, we will eventually be more targeted in our administration of stimulants for healing. For now, we give everything we have in the hope that the dreaded hammy injury can be reduced to a brief blip in the training program.